The Life & Death of New York’s Last Great Pool Shark

George “Ginky” SanSouci’s legend lives on, but his life was more troubled than many may have known

By Matt Caputo

The best pool players in the world filled the room: legendary New York City shooter Tony Robles was there; champion Jennifer Barretta and perhaps the world’s current best shooter, Mika Immonen. The occasion wasn’t a high-stakes shootout, a prestigious competition or a late-night action game. They were at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church on East 115th Street and First Avenue to bid farewell to George Edward SanSouci Jr., whom most knew as “Ginky.”

At just 39 years old, Ginky was known as one of the greatest pool shooters to ever live. On March 8, he was found dead at the apartment of his latest girlfriend in the Rego Park section of Queens. The cause of death is still undetermined, but those closest to him suspect Ginky expired after a long-term addiction to prescription pain medication.

In his life, Ginky was one of the game’s greatest natural talents and most beloved characters. His family says his life-long nickname was derived from the first words he ever uttered: “Ginky.” An enterprising New Yorker and a gambler by trade, he stumbled into pool in his late teens just as the Paul Newman and Tom Cruise film The Color of Money gave the sport a shot in the arm. Before long, Ginky had matured into one of the best pool players of his time.

At the table, Ginky took money from every other hustler and pool shark across the country. He claimed to have once gambled at the pool table for 42 hours straight. Known for his composure and mental toughness, Ginky earned a reputation few hustlers ever had. One story has it that Ginkywon $87,000 from one opponent and accepted $80,000, because the remaining sum would have bankrupted the other player.

“People would often lose thousands to him and buy him a drink and hug him afterward,” Edwin Gutkin, whom Ginky mentored until his death, says. “He was just that kind of a guy. He wasn’t a bad loser either.”

Only slightly matched by his thirst for gambling was his desire to compete. He excelled and earned fame at the tournament tables by winning major events like the Derby City 9-Ball Championship, the Camel Pro Billiard Series Ten-Ball Championship and the National Straight Pool tournament. In 1999, Ginky won the Billiards Congress of America Open, playing with a freshly installed metal plate where his neck met his back.

“I knew him since he first picked up a cue. He would ask me for a little advice and one time, a long time ago, he told me that I was his idol,” Robles says. “It’s funny how quickly roles get reversed, because not long after that I told him he was my idol. He had the work ethic of Michael Jordan.”

He also had a way with the ladies.

Even after his movie star-looks had faded, Ginky had dozens of girlfriends and could spark a conversation with nearly any woman.

“We were in Hollywood around 1996 getting a rental car, and Ginky met a black girl that was waiting for the bus,” remembers Stevie Moore, a former Bar Table world champion. “Ginky drove the girl home and she ended up hanging out with us the whole week. Ginky spent the night at her place. He brought the ladies in with his charm.”

But over the last few years, Ginky had been doing a lot of losing. As nagging neck injuries and a series of accidents cut into the prime of his career, he’d become even more hooked on the painkillers he’d begun using recreationally years ago. For the eight years leading up to his death, Ginky rented a narrow bedroom with a shared kitchen and bath in a private home in Jackson Heights. He’d spent any winnings he’d ever had, mostly on the prescription pain medication, and had taken to frequenting the pawnbrokers of Roosevelt Avenue when money became too tight. When he died, he had just $848 in cash to his name, all in his wallet.

“Sometimes he’d get a huge purse and he’d show up with gifts and he’d be on top of the world,” says his sister, Irene SanSouci McDonagh, whose three children–Erin, Jimmy and Jeanna—are devastated over the loss of their uncle. “Then there were other times where he’d be struggling to pay his rent.”

Growing up in the Yorkville section of Manhattan, Ginky didn’t always catch the best breaks. He was the quintessential latchkey kid who grew up break dancing and riding BMX bikes. He loved hip-hop and dyed his hair blond later in life as a tribute to Eminem, his favorite rapper. From an early age, he shunned school and spent the better part of his youth roaming the city. By junior year at Bayard Rustin High School for the Humanities, he’d quit school altogether. His parents were never married and his father, George SanSouci Sr., was in a fight at the age of 18 during which a knife damaged numerous vital organs. He died of his third heart attack at 29 years old, when Ginky was just 4. His mother, Jeanne, once a personal assistant to Tommy Hilfiger, raised him with the help of her older daughter, Irene. Jeanne died of cancer at 47, when Ginky was 24 and off playing in a tournament in California.

Ginky started playing pool in 1988 after finding his way to the now-defunct Chelsea Billiards, where he learned and studied the game. In its heyday, Chelsea Billiards was the type of place where degenerates loitered all day and flipped quarters at $100 a pop. He’d practice or gamble between eight and 15 hours a day. He’d follow Robles and other moreseasoned players to games around the city and worked his way into the elite class of shooters in just a few years.

When Amsterdam Billiards opened in March of 1990, owner Greg Hunt immediately sought out the best talent in New York.

“When you have the best players in the world playing in your room it puts you on the map,” Hunt says. “We saw him rise from being a top amateur to being one of the best pool players in the world, and some would argue that he was the best player in the world by 1999 or so.”

Ginky collected a string of state titles up and down the Northeast. The best run of his career was between 1995 and 2000. He was named Billiards Digest Rookie Player of the Year in 1995 and by 1999 had completed his personal-best high run of 343 straight shots at Slate Billiards on West 21st Street.

A number of injuries kept him from competition throughout his career. In 1997, Ginky fell off his motorcycle and injured his back. In a freak accident the next year, his shoulder was grazed when a love seat was thrown out of a four-story building near Amsterdam Billiards.

In 1999, he had surgery to repair discs in his neck, and by most accounts, Ginky underwent a total personality change. Before the pain meds took over, many remember Ginky’s drug of choice being Diet Coke and cheesecake. By the millennium mark, he was on a steady diet of Vicodin, Soma and Percocet. In 2001, Robles and other members of the pool community staged an intervention and got Ginky to agree to check into rehab.

“If somebody hadn’t done something, he definitely would have OD’d in 2002 because he did not realize what he was doing to himself,” SanSouci McDonagh says. “After rehab, he walked a straightline for a while.”

In August of 2003, Ginky met the then 17-year-old Athena Mennis, a waitress at the now-closed Racks Billiards in Astoria. The two began dating just as Mennis turned 18 and moved in together shortly after that. During the course of their relationship—which ended in June of 2010—Ginkymade sporadic attempts at sobriety.

“I didn’t allow anything in my house, and it was a constant battle with him,” Mennis says. “We were going to get married and the day after we got the license I found pills in our apartment. I had two miscarriages while I was with him. He started drinking after the first one because of it.”

Several attempts were made by family and friends to persuade Ginky to consider a second run at rehab. Although friends say he’d often get sober himself, they also knew he was given to impulsive binges. Still, Ginky was embarrassed by the stigma of going to rehab, especially for a second time.

Mennis claims that Ginky bribed doctors with $100 in cash to write him a script that he didn’t need. That cost, coupled with the cost of the pills themselves, created an expensive habit that left both Ginky and Mennis often broke. She says that between 1999 and 2003,

Ginky used aliases to obtain multiple prescriptions and drove all day to have them filled at different pharmacies.

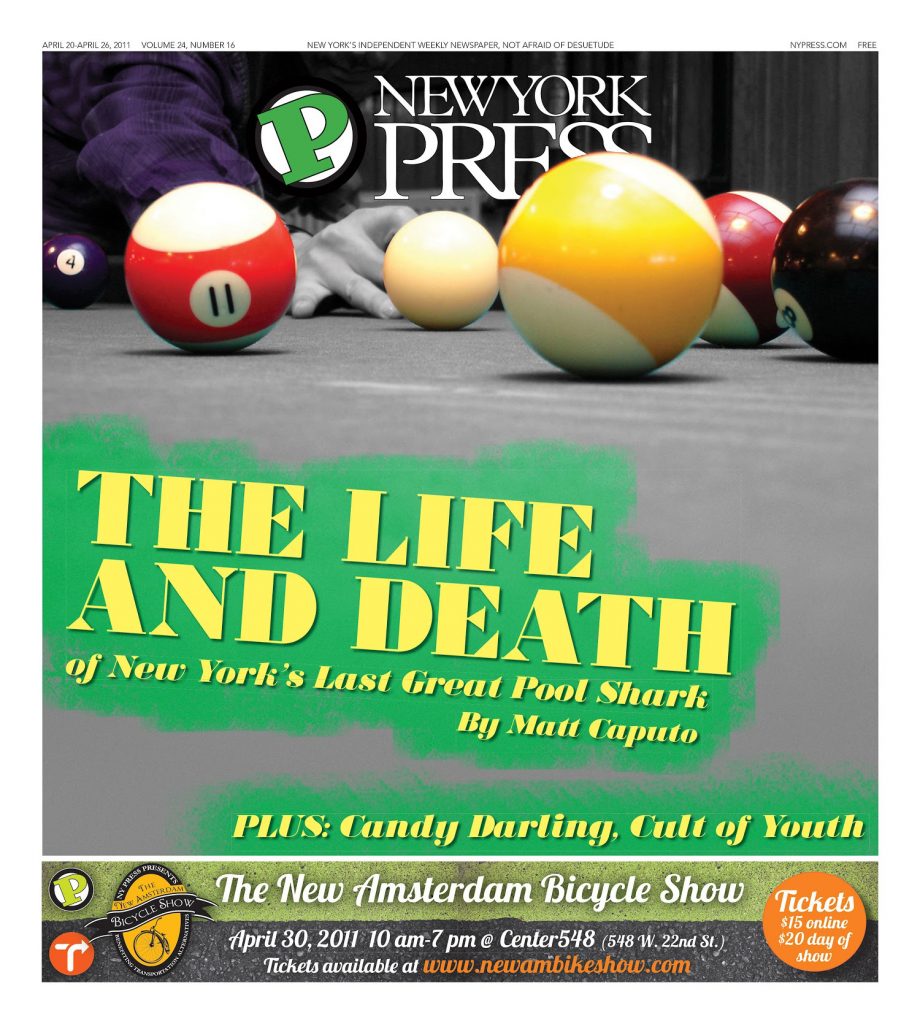

George “Ginky” SanSouci at the height of his talent.

Despite his own personal struggles with addiction, Ginky remained one of the most beloved members of the international pool community, known best for his kind gestures. He served as godfather to Robles’ son, Jonathan. In a 2005 handwritten letter to Barretta, he wrote, “I want to let you know if you don’t already, you are a Champion! Don’t ever quit. Maybe you lose, but don’t ever just give up. I want you to reread this letter. Words you might forget, but you’ll always have this letter to look back on.”

Ginky traveled to the WPA World Nine-Ball Championship in Cardiff, Wales, in 2001 to watch Immonen—still his rival—claim the first of his two world championships. Sitting in the stands, Ginky held a sign that read: “Finland’s Best is New York’s Finest,” as he cheered Immonen.

“He taught me a lot about the game and supported me when everyone else said I couldn’t do it,” Barretta says. “He wasn’t a perfect guy by any means, but he had a heart of pure gold and even the people that he did wrong still loved him.”

As his active playing career slowed, Ginky found he had few options to further himself. After rehab, his brother-in-law got him a job working as a doorman in 2002, but he quickly quit. The next year, he worked briefly as a cashier and house pro at the since-closed Master Billiards on Queens Boulevard, but he had too much pride to stick it out.

Ginky also had a hard time making good money games. The pool scene that he emerged from still existed, but the market for hustlers was getting smaller. Pool halls had closed slowly throughout the city, and there were fewer games for guys like Ginky to make their rent money playing in. All of the best money players in New York knew who Ginky was, and most were smart enough to stay out of high-stakes matches with him. Ginkybegan taking trips to North Carolina and using the alias “Eddie” in order to disguise his true identity.

“Another reason George was frustrated was that there was no action for him in New York. No one wanted to play him. He’d have to give up a huge handicap,”

Mennis explains. “He said once his face was in Billiards Digest magazine everyone knew who he was.”

In 2007, Ginky tried his hand at cards and lost. Aiming to cash in on the emerging poker craze, Ginky quickly fell in the hole for $20,000. Pool was his game and the best way he made a living, honest or otherwise.

“He was horrible at poker, pool was his game,” Mennis says. “He was going to poker rooms and playing online, pretty much putting us in debt.”

In early 2009, Ginky was clean and sober again after Mennis says she sent him to the psychiatric ward at Elmhurst Hospital for six days. When he got out, he had “Drug Free” tattooed on his left wrist as a constant reminder to stay clean. He wanted to make a comeback. He’d begun to take responsibility for his addiction. “It’s like someone who is drinking and driving. They think they’re driving safely because they think they’re normal, but they’re not as normal as they could be,” Ginky said in an interview available on go4pool.net, shortly after getting inked.

On April 21, 2009, Ginky and Mennis were driving on Sixth Avenue, heading to the 59th Street Bridge, when a cab driver blew a red light. Ginkyquickly turned the wheel to limit the impact, but his quick thinking only helped so much. He sustained a fractured left wrist while Mennis took the brunt of the blow. She suffered a fractured spine, lost three teeth and was burned by the air bag from nose to neck.

“I know that right after our car accident he was in pain,” Mennis says. “The pain wasn’t there before that.”

Prior to the accident, Mennis says Ginky had been sober for 180 days. She says the doctor prescribed both of them Vicodin and Ginky took both of their shares within a few days and was hooked again.

By June of 2010, Ginky and Mennis had split for good. Save for their involvement in the lawsuit from their car accident, their relationship had ceased. Soon after they broke up, Mennis claims to have begun casually dating rap superstar Drake and, upset by the news, Ginky decided to move on, too.

Though he was still saddled with a debilitating addiction to pain meds, the last year of Ginky’s life hadn’t been his darkest.

In November of 2010, he reunited with his somewhat estranged half-brother, Eddie Blacknick, and fit right in with the family he hadn’t really known. He never missed a chance to have his sister-in-law’s chicken wings and French fries. Blacknick’s children, Kaitlynn and Edward Jr., both quickly took to their loveable uncle.

“I never saw him intoxicated in any way, not while he was around me,” Blacknick says. “I never talked to him about pool, but he would talk to me a lot about my family and how he really wanted one of his own. He was just the greatest guy ever.”

Ginky started seeing a woman named Helene Zhu, she says, in late January. The two spent most of their time in pool halls,comedy clubs and at Zhu’s Rego Park apartment, where Ginky slept regularly. Although the two had only been seeing each other a short time, Zhu says Ginky was talking more and more about settling down.

“He was very happy. We did a lot of things together and he was playing in some tournaments,” Zhu says. “I know he wanted to go back into tournaments.”

He stayed involved in the game, even in new capacities. Since 2009, he’d served as celebrity referee of the Mega Bucks Nine-Ball Amateur Pool League championships and played friendly games against each member of the league at the completion of the finals. Despite his years of hard living and self-abuse, Ginky remained a star in the eyes of pool players who could only hope to emulate him.

“He did a phenomenal job, the guys loved him in our league here,” says Vincent Morris, who runs the Mega Bucks league. “The things he did in addition to what he should have done meant the world to me. It was tremendous, but I think he would have done something like that for anyone.”

Still, Ginky couldn’t quite kick his urges to get high. Three days before his death, Ginky had three prescriptions filled in his own name at Forest Drugs on Queens Boulevard in Forest Hills. The prescriptions—for 120 Endocet Tabs (Percocet), 100 Oxycodone and 30 tablets of the anxiety medication Alprazolam (Xanax)—were written by a Dr. Yakov Perper, whom Ginky had first seen immediately after the 2009 car accident. Although there were no refills indicated, Ginky was prescribed 100 Vicodin for 25 days and 120 Endocet tabs for 30 days. Family and friends question the motives of a doctor who would prescribe such a high dosage of strong medication to a patient with a history of addiction.

“Perper should have known that Ginky was addicted to pain medication because Perper worked at University Orthopedix when we told the doctors there that Ginky had a problem with prescription drugs,” Mennis says. “Perper had left the practice where we had originally met him, but Ginkyfound him.”

Zhu claims that Ginky suffered from sleeping problems and took something the night before he died.

“When he’s tired he can’t sleep and he took something to sleep,” Zhu says. “On Tuesday morning, he did wake up and I saw him, he was tired again and went back to sleep.”

Zhu says she couldn’t reach Ginky by phone during the day when she tried calling him from work. After returning home, she claims she called 911 and gave him CPR until the paramedics arrived.

“He was gone by then, I know that much,” Zhu says.

She was allowed to identify the body without the knowledge of Ginky’s relatives. Police later told Ginky’s family that he was found fully clothed and face down on the bed.

In the week following Ginky’s death, Amsterdam Billiards kept his favorite table, #9, empty for two days and sat a portrait of him on the felt. Donations poured in from every direction, including from events organized by players at both Amsterdam and at the Super Billiards Expo in Valley Forge, Penn., the week after he died. A person wishing to remain anonymous upgraded all of the details of Ginky’s funeral, including limousine services for the family from Manhattan to and from The Rose Hills Cemetery in Putnam Valley, N.Y.

Ginky’s sister, half-brother and Mennis all hope that any doctors who wrote Ginky bad prescriptions can be held accountable for writing scripts to someone who was obviously an addict.

Throughout his life, Ginky often scribbled in notebooks. “Sure, I have fucked up a lot. Yes, my neck surgery has gotten me addicted to pain meds, but everyday is a struggle. I fight it because I love my life, I love my career, and I love my family,” he wrote before he died. “I was lost for a very long time, even when I was on top of my game, after the surgery it just wasn’t natural. I was on painkillers all the time, and the memories are so hazy because my mind was fucked up.” Ginky died before he could collect any of the money from the lawsuit from the car accident that could have afforded him a fresh start. The billiard scene where he’d won and lost a fortune had little left to offer him. He’d already done it all.